Bad Bunny’s selection as the Super Bowl LX halftime headliner has detonated far beyond music, transforming a pop culture announcement into a national argument about race, identity, power, and who gets to define “American” entertainment on the world’s biggest stage.

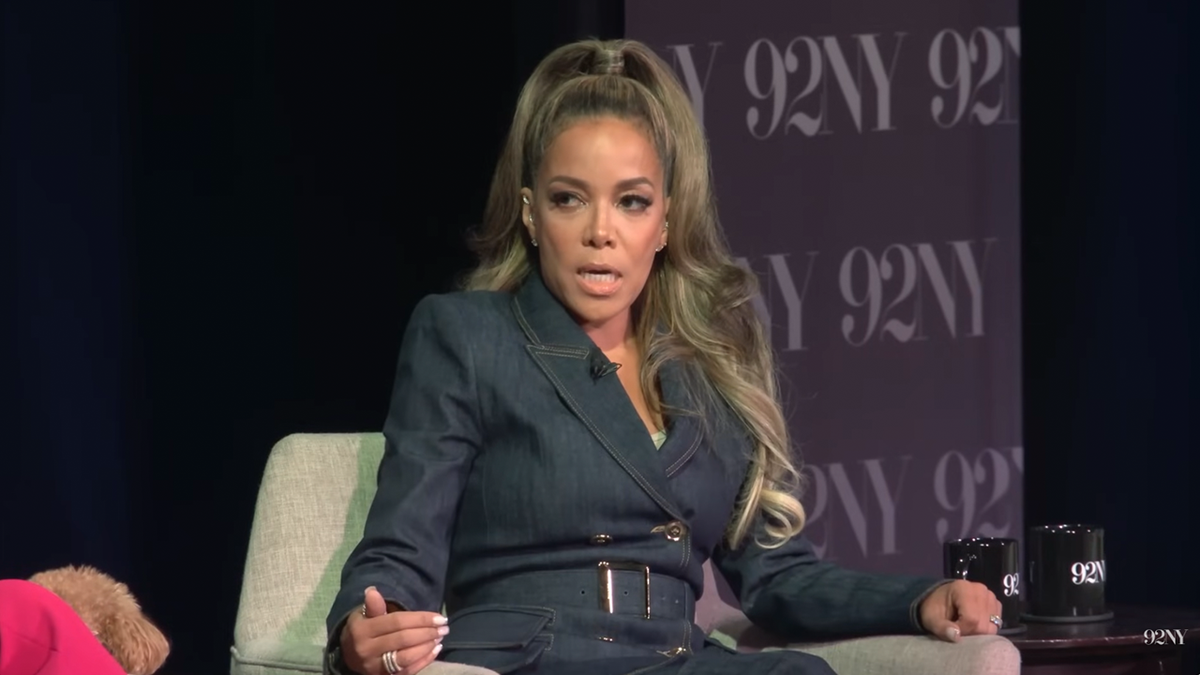

What might have once been a routine booking decision is now framed as a referendum on cultural belonging, especially after “The View” host Sunny Hostin forcefully declared that opposition to Bad Bunny’s performance is not musical criticism, but racism hiding in plain sight.

Hostin’s statement, “If you don’t want Bad Bunny to perform in the Super Bowl, you’re racist,” ricocheted across social media, cable news, and group chats, instantly dividing audiences into camps that see her words as either overdue honesty or reckless provocation.

For Hostin and her supporters, the backlash against Bad Bunny follows a familiar script, where global success by a non-English-speaking Latino artist is treated as an intrusion rather than a reflection of modern American culture.

Bad Bunny, born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, is not an underground experiment or niche act, but one of the most streamed artists in the world, commanding stadiums, charts, and cultural relevance across continents and languages.

Yet critics argue that popularity alone should not shield an artist from scrutiny, insisting that fans should be allowed to dislike a performer’s style, language, or symbolism without being branded as morally defective or socially regressive.

This argument intensified when Turning Point USA announced plans for an alternative “All-American Halftime Show,” headlined by Kid Rock, framing the move as a response to what they described as cultural alienation.

To supporters of Bad Bunny, this counter-programming felt less like harmless preference and more like a deliberate cultural protest, signaling discomfort with a Super Bowl stage that no longer centers traditional white, English-speaking rock archetypes.

Kid Rock’s involvement further escalated tensions, given his long-standing association with conservative politics and culture-war rhetoric, making the contrast between the two halftime visions feel intentionally symbolic rather than coincidental.

Sunny Hostin did not mince words on “The View,” asserting that attempts to replace or undermine Bad Bunny’s performance reflect an unwillingness to accept that America’s identity has evolved beyond narrow historical definitions.

She framed the controversy as part of a broader resistance to demographic and cultural change, arguing that Latin music’s global dominance threatens outdated hierarchies that once dictated whose voices were considered mainstream.

Critics of Hostin’s stance countered that her accusation oversimplifies a complex conversation, warning that labeling disagreement as racism risks silencing legitimate debate and hardening divisions rather than fostering understanding.

Social media, predictably, poured gasoline on the fire, with hashtags supporting Bad Bunny clashing against calls for “choice,” “tradition,” and “real American music,” each side convinced the other was acting in bad faith.

What makes this moment uniquely volatile is the Super Bowl’s symbolic weight, functioning not just as a football championship, but as a televised snapshot of American values broadcast to hundreds of millions worldwide.

Every halftime show carries implicit messaging about who belongs at the cultural center, which is why previous performances by artists like Beyoncé, Shakira, and Rihanna also sparked debates extending far beyond choreography or vocals.

Bad Bunny’s upcoming performance intensifies that pattern, because his Spanish-language dominance challenges lingering assumptions that English remains the uncontested language of American mass culture.

Supporters argue that rejecting Bad Bunny ignores demographic reality, as Latino audiences represent one of the fastest-growing and most influential segments of both the American population and consumer economy.

From this perspective, resistance is not neutral taste but discomfort with visibility, particularly when cultural power shifts toward communities historically marginalized or expected to assimilate quietly.

Opponents push back by insisting that patriotism, tradition, and shared cultural touchstones matter, and that rapid change can feel alienating rather than inclusive to many long-time viewers.

This emotional undercurrent explains why the controversy feels so personal, with fans and critics alike interpreting the halftime show as a statement about whose stories matter in America’s most watched spectacle.

Media outlets quickly recognized the viral potential, amplifying soundbites and framing the story as a culture war showdown, virtually guaranteeing algorithmic traction across platforms hungry for outrage-driven engagement.

In this environment, nuance struggles to survive, as complex discussions about art, identity, and representation are compressed into slogans, clips, and reaction videos optimized for maximum emotional impact.

Sunny Hostin’s remarks, while polarizing, tapped into this ecosystem perfectly, offering a clear moral framing that supporters could rally behind and critics could vehemently reject.

For Bad Bunny himself, the controversy may be both burden and boost, reinforcing his status as a cultural lightning rod whose influence extends far beyond music charts and tour sales.

Historically, Super Bowl halftime performers often become symbols of their era, remembered as much for what they represented socially as for what they delivered musically.

Whether audiences cheer, boycott, or argue online, the halftime show has already succeeded in commanding attention, ensuring that Super Bowl LX will be discussed long before kickoff and long after the final whistle.

This raises uncomfortable questions about whether controversy is now an unofficial prerequisite for cultural relevance, especially in an attention economy where silence is the only true failure.

Some viewers long for a return to simpler entertainment debates, focused on performance quality rather than ideological alignment, though such nostalgia may underestimate how long culture and politics have been intertwined.

The Bad Bunny debate ultimately exposes competing visions of America, one viewing diversity as enrichment, the other perceiving it as displacement, both convinced they are defending something essential.

As the Super Bowl approaches, the noise will likely intensify, with pundits, politicians, and influencers eager to insert themselves into a conversation that reliably generates clicks and loyalty signals.

What remains uncertain is whether viewers will watch the halftime show seeking confirmation of their beliefs, or allow themselves to experience it simply as music, performance, and spectacle.

In the end, Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl moment may reveal less about the artist himself and more about the anxieties, hopes, and unresolved tensions shaping American culture right now.

Because when a halftime show becomes a national argument, it is no longer just about who is on stage, but about who feels seen, heard, and valued when the lights are brightest.

News

From my hotel room, I saw my sister’s dress hitched high as she pressed against my fiancé. ‘Just try me once before you decide,’ she whispered. I felt sick as I continued recording, my hand shaking. Families burn, recordings last.

From my hotel room two hundred miles away, I watched my life split open on the screen of my iPad….

MY HUSBAND FORCED ME TO ORGANIZE A BABY SHOWER FOR HIS MISTRESS—BUT WHAT THEY DIDN’T KNOW WAS THAT THE “GIFT” I PREPARED WAS A DNA TEST THAT WOULD SHATTER THEIR PRIDE.

MY HUSBAND FORCED ME TO ORGANIZE A PARTY FOR HIS MISTRESS—AND WHAT I GAVE THEM SHATTERED THEIR ENTIRE WORLD My…

At our divorce hearing, my husband laughed when he saw I had no lawyer. “With no money, no power, no one on your side… who’s going to rescue you, Grace?” he sneered. He was convinced I was helpless..

At our divorce hearing, my husband laughed when he saw I had no lawyer. “With no money, no power, no…

My Stepmother Forced Me to Marry a Rich but Disabled Man..

My Stepmother Forced Me to Marry a Rich but Disabled Man — On Our Wedding Night, I Lifted Him Onto…

Poor Girl Tells Paralyzed Judge: “Free My Dad And I’ll Heal You” — They Laughed, Until She

The heavy, suffocating silence that descended upon the packed courtroom was absolute. For a heartbeat, it seemed as though every…

I gave part of my liver to my husband, believing I was saving his life. But days later, the doctor pulled me aside and whispered words that shattered me: “Madam, the liver wasn’t for him.”

I gave a part of my liver to my husband, believing I was saving his life. But just days after…

End of content

No more pages to load