The boy stood barefoot on his frozen shoulder, his lips blue, waving at the car’s headlights and shouting that he had to find “the man with the watch” before midnight.

I barely saw it.

New Year’s Eve, mile marker 183, slush like nails, the county’s only snowplow dead in a ditch, its yellow light still spinning. I was driving slowly in the Softail, the engine roaring like a faithful dog, coming back from a coffee-and-eggs run at Dolly’s Diner because the clubhouse stove had broken down an hour earlier. The road was a gorge of black ice and bad decisions, one of those nights when you feel God’s breath on your neck.

Then I saw a small shadow with legs.

The boy turned to me, his hands raised, tears freezing on his cheeks. He was barefoot. His coat was gone. His jeans were soaked to his knees. He looked about eight, maybe nine, the age when you still believe in magic and also know how ugly the world can be.

I braked so hard the rear wheel skidded. The bike settled. I put my boot down and ended up between him and the road.

“Hey,” I said. “Hey, calm down.”

He stared at my vest, my beard, the skull patch with white thread, the Iron Cross pin, the road salt on my boots. I know how most people see me: a problem that learned to walk.

He didn’t flinch.

“Do you have a name?” I asked.

“Caleb,” she said, her lips trembling. “I have to find the man with the watch.”

“What watch?” I said, even though I already knew.

He didn’t answer. His gaze fell on my left forearm, where the sleeve of my sweatshirt had slipped beneath the leather. The tattoo is a clock face in black and ash shading, a spiderweb of cracks in the glass, with the hands fixed on twelve. I got it fourteen years ago, the last time I drank myself dry.

Caleb saw the ink and folded it like a paper cup.

He hit my chest and shook with a sound that wasn’t really crying, but more like an animal that knows the trap has closed. I wrapped him in my vest. His ribs looked like firewood.

“Where are your parents, Caleb?”

“My dad,” he said against my shirt. “He’s dying. He said, ‘If anything happens at midnight, find the clock man. He’ll keep you safe.’”

He looked up. The sleet formed stars in his hair.

“Are you him?”

I stared at the road, the wind, the lost years that smelled of gasoline, of courts already lost. Somewhere behind my ribs, something old and rusty turned around and came to life.

“Maybe,” I said.

I didn’t ask him why he was alone on the highway. I didn’t ask him how far he’d gone. It was 11:06 on the green light on the dashboard. The sleet got louder. Big trucks roared past, throwing up knives of sleet.

I took off my sweatshirt and put it on him, and then my vest over it. Vests aren’t about fashion. They’re about belonging. On the back of mine, a white skull with wings on a wheel and a banner: IRON SAINTS, MID-COUNTY.

—Get in—I told him—. We’re going to see your dad.

He hesitated. Then he clenched his jaw the way I’ve seen men do before stepping into fire and swung a skinny leg over the seat. He wrapped his arms around me and pressed his face between my shoulder blades. I felt his breath through the leather.

It was going slowly, eighty horses trying to dance on the windshield. We took the exit toward town because the hospice is across the street from Walmart, and death is the only business that never closes. Three kilometers ahead, blue lights flashed. The sheriff’s Ford with its fogged windows, two deputies standing with steaming coffee in their hands. They saw me, they saw the kid in my vest, and their faces hardened.

“Good night,” I said.

“Good evening, Rook.” The sheriff narrowed his eyes at Caleb. “What’s this?”

“He’s becoming like his father.”

“Where did you pick it up?”

—Highway —I said—. Kilometer 183.

The younger assistant nodded to Caleb. “Are you okay, son?”

Caleb squeezed my waist.

“We can handle this from here,” the sheriff said.

“Respect, Sheriff,” I said, keeping my hands where he could see them, “but we won’t stop.”

“That’s not your decision.”

“No way!” I said, but the wind cut me off. “You have until midnight.”

The sheriff looked at the vest, the patch under my name: SGT-AT-ARMS. He looked at my left arm, where the watch showed the time despite the sleet. His eyes moved slowly.

“Torre,” he said in a lower voice. “Is he family?”

That word broke something I didn’t know was frozen.

—Yes —I said—. It is.

The sheriff nodded once, like someone pronouncing a sentence he didn’t believe in.

“Then go,” he said. “But Rook…”

“Yeah?”

“I didn’t see you.”

We set off. The hospice is in a square building with new shutters and old sorrows. I parked on the red sidewalk. Caleb slid on the melting snow and felt nothing. He ran toward the doors. The heat inside made him stagger. The woman at the counter raised a hand.

“Visiting hours have ended.”

“Not anymore,” I said.

“Sir, you can’t simply—”

“Madam,” I said, and placed my hand on the desk, the clock face upside down and the shattered crystal in my veins. “You’re going to want to make an exception.”

He looked at the tattoo. Some people see the ink and see a bad decision. Others see a story. He picked up the phone without taking his eyes off me. “Room twelve,” he told Caleb. “At the end of the hall, on the right.”

He ran.

I slowed down, my bones stiff and my shoulders tense. The hallway smelled of lemons, after all. Soft shoes squeaked. A television somewhere was flickering on a football match no one cared about, its color so strange you’d think all the players were dying too.

Room twelve was dimly lit. The machines hummed their small, useless prayers. In the bed was a man whose face I recognized even before the light reached him.

“Ethan,” I said.

Her eyes opened like doors that had been opened too many times.

“Torre,” he said, and the past fell between us like tools from a broken toolbox: nights behind the church, cigarettes at thirteen, a Buick without a muffler, a fight at the lake, his hand on my shoulder the day I left and never came back.

My little brother. Gray at the temples. A scar on his mouth that I didn’t recognize. I took a step and all the miles kicked me in the knees.

“Dad,” Caleb said from the bed, his small hand wrapped around larger fingers that were already forgetting how to be hands. “I found it.”

Ethan looked at Caleb, then at me, and the look he gave me could have returned the oceans to their beds.

“Good boy,” he whispered to his son and me: “You’ve come.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

She smiled as if it hurt her, but it was worth it. “You were always late.”

A nurse came in and looked at the wall clock. It was 11:27. She did what they do when there’s nothing they can do. She left. There were three of us in the room, and time sat us down in a chair with our coats on.

“I didn’t know anything about him,” I said, nodding at Caleb.

“I didn’t know where to find you,” Ethan said. “I only had the story. The man with the watch. People always knew you for that.”

“I’m not…” I began, and stopped because lies need to be watered and I’ve already watered too much.

“You’re what he needs,” Ethan said. “Tonight, that’s enough.”

The machines made tiny metronomes. Sleet pattered against the window. Somewhere in the building, someone was laughing, and that’s how sadness stays human.

“Who told you to go out on the road?” I asked Caleb.

“Dad,” Caleb said. “You said if things got bad and I woke up and you were gray, I should run and find the clock man. I left through the back because the receptionist told me I couldn’t leave through the front without adults.”

Ethan closed his eyes. “Always stubborn,” he muttered, and I couldn’t tell which of the two he meant.

“We need to call a doctor,” I said.

“He knows it,” Ethan said. “This is the part where nothing stops.”

He turned his head like he did when he was ten and asked me for help. I told him we’d be okay as long as we kept going. “Promise me, Rook.”

I felt the weight of the leather on my shoulders, the patch on my back, the path in my blood, the old oath we made in a garage the color of spilled oil: I lie down; you lift me up. I fall; you carry me. The world says we’re wolves; we show them what wolves do to theirs.

“I promise,” I said.

“Keep him safe,” Ethan whispered. “No matter what it takes.”

The clock on the wall made a noise as loud as a gunshot.

11:49.

I sent a text message with one word to the Iron Saints thread.

MIDNIGHT.

The answers came quickly, gray bubbles of men who had done terrible things and beautiful things and carried both like coins in the same pocket.

In it.

Lamination.

You got it, Sergeant.

I stood by the window and watched the sleet turn into snow, thick flakes that made the world seem cleaner than it was. A minute later I saw the first headlight. Then another. Then the curve of the parking lot filled with a dull rumble that sounded like the inside of my chest.

The brothers rode slowly in a circle around the hospice, the tires crunching and the pipes rattling. A circle of bicycles in the snow, a belt of iron and noise, and men getting off and standing with their hands folded over the belt like deacons around a bed. Some carried their daughters on their shoulders, sons in sweatshirts, wives with coffee. The town that calls us trash and angels, depending on the day, arrived and stood still in the cold and the falling fog.

No one asked the sheriff for permission. Nevertheless, he pulled over and parked next to the light pole, leaning against the hood, watching with his collar rolled up and his cap down.

The nurse returned with tears in her eyes. She adjusted things, and then she didn’t.

Ethan’s breathing took small steps and then rested.

“Caleb,” she whispered. “Do you remember what I told you about the watch?”

Caleb nodded, his throat twitching. “You said midnight is just a doorway.”

“That’s right,” Ethan said. “And you don’t go through the doors alone.”

I took her hand and Caleb’s hand and made a rope of blood and bone between us.

11:58.

The building was silent, with that special calm that fills the air when something crucial is about to happen. Snow was falling on the parking lot. In the circle, my brothers took off their caps. We don’t usually kneel much. Back then, we did.

Ethan looked at me. “Do you still have it?”

“Have to?”

He smiled. “Your watch.”

The watch tattooed on my arm is a reminder of one I pawned for whiskey. He knew it. He knew everything. He always knew.

“No,” I said. “I don’t know.”

“Yes, I do,” he said.

She nodded toward the nightstand. In the drawer was a cheap stainless-steel pocket watch with a crack in the face. The hands were broken at the number twelve. I turned it over. On the back was an inscription in crude lettering that had eaten away at the metal: “YOU WERE THERE WHEN IT MATTERED.”

I just stared.

“Whose?” I asked.

Ethan’s gaze held that intensity that fades when the room you’re in isn’t the same one you left. “The night I turned eight,” he said slowly, as if he were lowering a photograph. “Remember, Rook? Mom hadn’t come home. I was on the stairs with a fever. You wrapped me in your coat and carried me five kilometers to the clinic. You lost your job. You were fired. You walked home in the rain. You always thought I’d forgotten.”

“I didn’t do it,” I said, and the ground inside me buckled.

“I made this for you when I was nineteen,” he murmured. “I couldn’t find you. So I kept it. I figured if you came back, I’d recognize you. I told Caleb that if I ever found the man with the watch, I’d find you.”

The clock on the wall ticked so loudly it was a metronome of pain.

11:59.

Ethan’s fingers tightened around ours and then he let go.

The second hand made a long loop.

He arrived at twelve.

The building sighed. The circle of motorcycles in the darkness revved once, without much noise, just enough to create an atmosphere that felt like the inside of a church.

Ethan exhaled and did not inhale.

I placed my hand on her hair and closed her eyes.

The ground shook, but it was only me.

Caleb didn’t make a sound. He climbed onto the bed, rested his head on his father’s chest, and listened to what wasn’t there. His shoulders twitched. I pressed my face to my palms and remembered all the times I hadn’t been there for anyone, and I vowed aloud that those times were over.

The nurse came back with a doctor. The paperwork was done. It always happens. She slipped into the room and tried to wrap the child. “We’ll have to call Child Protective Services,” the nurse said quietly, as if she were telling me to tip my hat in church. “It’s policy.”

“Politics,” I said, savoring the word like a moth.

The doctor looked at my vest and then at the circle of brothers outside. “Perhaps we can wait until tomorrow,” he said, surprising himself with his own courage.

But the phone was already ringing on the counter, and politics puts on heels when it wants to.

Two hours later, after the bodies had been removed and the forms filled out, a woman with her hair in a tight bun and her mouth even tighter told me that Caleb needed to accompany her to a “placement.” She pronounced the word as if she were placing a package on a conveyor belt.

“It’s not a package deal,” I said.

She pursed her lips. “You’re not family.”

“I’m his uncle,” I said, and the truth echoed in the air like a bat colliding with a fastball.

“Try it.”

I picked up my pocket watch. “He just did it.”

It didn’t matter. Politics doesn’t blink. She grabbed Caleb’s shoulder, and my brothers intervened. Not with fists. With phones. With lawyers’ numbers. With a pastor who married half the town. With the sheriff coming in, putting his hand on her arm and saying, “Why don’t we all just breathe?”

We sat in the hospice lobby as the snow replenished the parking lot. The woman made calls. I made calls. The Iron Saints claimed all the favors we’d earned fixing transmissions cheaply, shoveling Mrs. Danner’s sidewalk, and tossing Christmas ornaments under trees that had been ashamed of themselves the day before. At dawn, a frosted-eyed emergency judge uttered the words “temporary guardianship,” “family placement,” and “review hearing.”

Caleb fell asleep in a plastic chair with my vest draped over him like a flag.

When we finally got outside, the sun was barely a faint whisper over the Walmart sign. Motorcycles crept along, a line circling my Softail. People in minivans stopped and stared at me. Some put their hands to their hearts. Others locked their doors. Everyone’s a critic.

The following weeks were filled with paperwork, pain, and small victories. We emptied the tiny apartment Ethan had rented: a sofa, two plates, three comic books, a jar of screws the size of a galaxy in a glass case. We found a photo of him and me as children, both of us smiling with mouths full of missing teeth, his arm around my waist as if he were worried I’d blow away.

Caleb got a room in my house. He wouldn’t hang a moon poster until I showed him how a stud finder worked. He didn’t want a nightlight. He wanted the hall light, the bathroom light, the porch light—all the lights—and I bought the extra bulbs without a word.

The social workers came and checked my knives, my patches, and my life. They frowned at the rag I used for everything. They smiled at the charts I made with my chores. They asked about my history, and I told them. They asked about my sobriety, and I gave them cards with the date and my sponsor’s phone number. They asked if Caleb would be safe with a biker.

“You’re asking the wrong question,” I said. “Ask him if he will be loved.”

They wrote it as if it were a threat. Then they came back and saw me burning pancakes, teaching Caleb how to change the oil, taking him to the river to throw rocks at what had hurt us, and standing on the courthouse steps for the hearing in a button-down shirt that felt like it was coming off a bar fight. The judge looked at the letters the community had written, the sheriff’s nod of approval, the pastor’s hand on my shoulder, and the pocket watch I kept in my vest like a heartbeat.

The hammer made a sound like a door closing behind the past.

I took a breath.

We went out at midday in the winter. The brothers were waiting on the steps, a crooked honor guard of men with lives heavier than they let on. They didn’t cheer. They don’t cheer unless the ball goes over the fence. But they took off their caps again, and that was better.

On the first day of spring, Caleb and I rode the Softail to kilometer 183. The roadside had traded ice for last year’s water bottles. The grass had that waxy green that still seems unbelievable. We parked and walked along the shoulder where he had run with the cold fingers of God pressing against his ears.

Caleb stood there, his shoes untied, watching the long ribbon of America recede into the distance, toward places we hadn’t yet been. He took my hand without looking at me. I gave it to him.

“Midnight is just a door,” he said.

“That’s how it is.”

“And you don’t go through the doors alone.”

“Not anymore,” I said.

That night, in the clubhouse, the Saints brought a broken clock out of storage. Someone had found it under a sheet of metal. It was missing a hand. The crystal was covered in cobwebs. I watched the men with whom I’d shed blood lean over that clock and argue about paint and polish with tongues as sharp as razors and hearts as soft as bread.

We screwed it to the front wall, well above the roller door.

At midnight, we accelerated once, just enough to send a sound along the river, over the rusty railway bridge, and through the alleyways where men sleep in their boots. It was an old church bell with a smell of gasoline.

People began to talk. They said the Iron Saints had surrounded the hospice and banished the darkness. They said a boy found his guardian on the coldest night in ten years. They said everything they thought they knew about wolves and clocks was wrong.

Caleb asked me if heroes always look like heroes.

“Almost never,” I said.

“What are they like?”

I thought of my little brother’s hand, still warm at the end. I thought of the sheriff watching with his hat down. I thought of a circle of men in the snow, their heads bowed before a shared miracle.

“They seem like people who stay,” I said.

At the end of that year, we put rubber bands around the paper tree that made us a family and went to Dolly’s for eggs. The waitress put down two plates and slid a third onto the empty chair.

“For your brother,” he said.

We ate. We paid. We left a tip that made the waitress wipe her eyes and pretend it was a draft.

At 11:59, Caleb and I were in the garage, under the large clock. The brothers were with us. The second hand ticked. The bagpipes droned on in a soft, continuous prayer.

The hand pointed to twelve.

Caleb looked up and smiled at me, and I felt that old, rusty thing inside me run clean like a river in April.

“Are you ready?” I asked.

He put on his helmet. He adjusted his gloves with small teeth. He climbed in and hugged me as if they had always been there.

We rolled into the cold, under a sky full of harsh, bright stars, and for the first time in my life, the New Year felt like a promise I had a right to keep.

People in the county started calling me names I never thought were appropriate.

Guardian.

Legend.

Midnight Saint.

I’m just Rook. A man with a watch on his arm that reminds him of two things that are true in any language: time runs out, and love doesn’t.

News

“Sir, that boy lives in my house” — What he said next caused the millionaire to break down

Hernán had always been one of those men who seemed invincible. Business magazines called him “the king of investments,” conferences…

A MILLIONAIRE ENTERS A RESTAURANT… AND IS SHOCKED TO SEE HIS PREGNANT EX-WIFE WAITING

The day Isabela signed the divorce papers, she swore that Sebastián would never see her again. “I swear you’ll never…

Emily had been working as a teacher for five years, but she was unfairly dismissed…

Emily had been working as a teacher for five years, but she was unfairly fired. While looking for work, she…

A billionaire lost everything… until his poor daughter, a black maid, did the unthinkable… – bichnhu

A billionaire lost everything, until his poor son, a black maid, did the unthinkable. The computer screen lit up red…

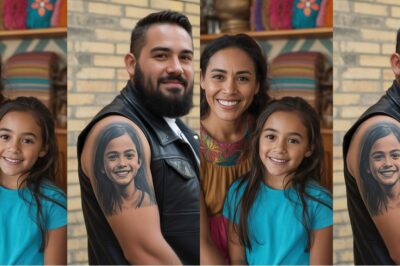

“Eight years after her daughter disappeared, a mother recognizes her face tattooed on a man’s arm. The truth behind the image left her breathless.”

One afternoon in early July, the boardwalk in Puerto Vallarta was packed. Laughter, the shouts of playing children, and the sound of…

As my husband beat me with a golf club, I heard his mistress scream, “Kill him! He’s not your son!” I felt my world crumble… until the door burst open. My father, the ruthless CEO, roared, “Today you’ll pay for what you did.” And in that moment, I knew… the real storm was just beginning.

As my husband, Andrew , beat me with a golf club in the middle of the living room, I could barely protect…

End of content

No more pages to load