Sterling Vance fired his entire housekeeping staff in under 10 minutes. It wasn’t the broken vase in the hallway. It wasn’t the wrinkled shirts hanging in his closet. It was the candles. He had walked through the front door of the iron mill after 14 hours of negotiations that would make or break a $2 billion merger.

And the first thing that hit him was the smell. Vanilla. Sweet cloying suffocating vanilla where there should have been cedarwood. The head housekeeper, a woman named Patricia, who had come highly recommended by three senators and a Supreme Court justice, stepped forward with a practice smile. Mr. Vance, I thought the house could use something warmer.

Vanilla is known to reduce stress. And who asked you to think? Patricia’s smile faltered. I beg your pardon? The cedarwood candles? Sterling’s voice was quiet. He never raised his voice. Where are they? We disposed of them. They were nearly empty and I thought, “There’s that word again.” He set his briefcase down on the marble console table, thinking, “Consideration, care.

” He looked at her directly for the first time. Misplaced consideration is a form of noise, Patricia, and I despise noise. Mr. Vance, I was only trying to You’re fired, all of you. Five people, five careers gone in the time it took to change a candle. The story spread through Seattle’s elite circles by morning. Candles.

Eleanor Whitmore repeated at her charity lunchon, her fork suspended midway to her mouth. He fired five people over candles. “I heard it was because they rearranged his books,” said Margaret Chen, who made it her business to know everyone else’s business. “No, it was definitely the candles,” insisted Dorothy Hayes. “My daughter’s roommate’s cousin works at the staffing agency.

Apparently, the man is impossible. Absolutely impossible. gorgeous, obscenely wealthy, and completely unhinged. “He’s not unhinged,” said Victoria Lane, the only woman at the table who had met Sterling Vance in person. She was the wife of a tech CEO and had once sat next to him at a fundraiser. “He’s empty. You can see it in his eyes, like looking into a room where someone turned off all the lights and forgot to come back.

” The other women fell silent, uncomfortable with the observation’s precision. 300 m away in a cramped office above a laundromat in Portland, a woman named Helen Marsh was having a very different conversation. “This is the seventh agency he’s burned through in 18 months,” Helen said, sliding a folder across her desk.

“The man is a walking disaster.” “Will Chen didn’t reach for the folder. She sat with her hands folded in her lap, her posture straight but relaxed, her dark hair pulled back in a simple ponytail. Nothing about her demanded attention. “That was the point. What did the others do wrong?” Will asked. “They existed.

” Helen leaned back in her chair. Sterling Vance doesn’t want a housekeeper. He wants a ghost. Someone who cleans his house, maintains his schedule, anticipates his needs, all without ever being seen, heard, or acknowledged. Then why does he keep firing people? Because they keep trying to be helpful, to be noticed, to be human. Helen tapped the folder.

But you’re different, Willa. In 5 years, I’ve never had a single complaint about you. Not one client has ever mentioned you at all, which in this business is the highest compliment. Will his lips curved slightly. I like being invisible. Good, because that’s exactly what this job requires.

Helen pushed the folder closer. Don’t let him see you. Don’t let him hear you. Don’t leave any trace that you were ever there. Can you do that? How much does it pay? Helen named a figure that made Willa’s eyes widen. I’ll do it. As Willa reached for the folder, her sleeve rode up slightly. Helen caught a glimpse of something on her finger.

A ring, though it looked strange. Homemade copper wire twisted around a piece of sea glass. She filed the observation away and said nothing. Some things were none of her business. The iron mill was everything the rumors had promised and nothing like Willa expected. It sat on a cliff overlooking the Pacific, all steel beams and floor to ceiling glass.

A fortress designed to intimidate rather than welcome. Willa arrived at 5:30 in the morning when the November fog still clung to the cliffs, and the mansion looked like something rising from a Gothic nightmare. The previous staff had left in chaos, dishes piled in the sink, dust gathering on surfaces. A halfeaten meal abandoned on the kitchen counter, growing something green.

Willa got to work. She removed her shoes at the door, replacing them with thick wool socks that silenced her footsteps on the hardwood floors. She found the storage room and located a half empty box of cedarwood candles, pushed into a corner as if someone had tried to make them disappear. She placed them exactly where the vanilla candles had been, matching the wax levels to the rings they’d left on the surfaces.

She noticed the lights were too harsh.clinical white that probably triggered the migraines she’d read about in the business profiles. She adjusted the smart home system room by room, shifting from cold white to warm amber, reducing the intensity by 20%. In the kitchen, she placed a glass of water infused with cucumber and lemon beside his coffee maker, not to replace his coffee, just to offer something gentler.

By the time she finished, the sun was setting over the Pacific. She had worked for 11 hours. She had not eaten. She had not sat down. She had not made a single sound. She left through the service entrance and disappeared. Sterling came home at 8. He stopped in the foyer. He didn’t move for a long time. The lights were different.

The smell was different. The entire atmosphere of the house had shifted in a way he couldn’t quite name. It felt less like walking into a museum and more like walking into something else. somewhere he might actually want to be. He walked through the rooms slowly, searching for evidence of the intruder. There was none.

No fingerprints on the polished surfaces, no indentation on the cushions, no lingering scent of perfume or shampoo. In the kitchen, he found the water with cucumber and lemon. He stared at it for a long moment, then drank it in three swallows. In the living room, he discovered that the cedarwood candles had returned.

He lit one and watched the flame dance. Something stirred in his chest, something old and buried and dangerous. He pushed it down. That night, Sterling fell asleep on the sofa without pills or whiskey. He simply lay there watching the candle flicker and let the silence carry him away. Two weeks passed. Sterling never saw his new housekeeper.

She was a ghost, just as Helen had promised. The evidence of her existence was everywhere. the perfectly pressed shirts, the fresh flowers that appeared and disappeared without explanation, the way his coffee was always ready at exactly 6:47 a.m. But the woman herself remained invisible. Sterling found himself watching for her, setting traps, coming home early or leaving late, hoping to catch a glimpse.

But she always seemed to know, always seemed to be one step ahead, always vanished before he stopped himself. Why did he care? This was exactly what he wanted. A housekeeper who didn’t exist. A ghost who served without being seen. So why did the house feel warmer than it had in years? The day everything changed started like any other.

Sterling woke with a headache and a low-grade fever. The first sign of weakness his body had shown in months. He canceled his meetings, told his assistant he would work from home, and retreated to his study with his laptop and a determination to power through. He was reviewing quarterly reports when he heard it. Nothing. Absolute silence.

But the silence had a quality to it now, a presence. Someone was in the house. He minimized his spreadsheet and pulled up the security feed on his secondary monitor. There she was in the living room cleaning his antique oak desk with slow, careful strokes. She was smaller than he’d expected, slighter. Her dark hair was pulled back in that practical ponytail he’d imagined, and she wore a simple gray uniform that seemed designed to make her forgettable.

She moved through the space like water flowing around stones, never disturbing anything, simply existing in the gaps. The afternoon light, rare for November on the Oregon coast, suddenly broke through the clouds and poured through the window. It fell across her hands. Sterling stopped breathing. The ring was unmistakable.

copper wire twisted and bent in the clumsy way of a child who had never worked with metal before. At its center, a piece of sea glass, pale blue, worn smooth by ocean waves, the same pale blue as Sterling’s eyes. The glass of water in his hand trembled. He set it down carefully, afraid he might drop it. No, it’s not possible. It can’t be her.

But the ring, that ring, he would know it anywhere. Even after 20 years, even after a lifetime of trying to forget. 20 years ago, Mercy House Children’s Home. Portland, Oregon. The junkyard behind the orphanage smelled like rust and broken promises. Sterling just stir back then. A skinny 12-year-old with dirty fingernails and a chip on his shoulder was supposed to be at dinner.

Instead, he was crouched behind a pile of scrap metal working on something that would get him a beating if the housemothers found out. What are you making? He nearly jumped out of his skin, but it was just Willa. 10-year-old Willa Chen with her crooked braids and her handme-down dress and her eyes that saw everything.

“Go away,” he said automatically. “She didn’t go away. She never did. Instead, she crouched down beside him, her knees touching the dirty ground without hesitation.” “Is that a ring?” “It’s supposed to be.” He held up the mess of copper wire, frustration tightening his jaw. But I can’t make it look right. It keeps coming out ugly.

Will reached into her pocket and pulledout something small. A piece of glass worn smooth by the ocean. The pale blue of a summer sky. I found this on the beach trip, she said. Sister Mary said I couldn’t keep it, but I hid it in my shoe. She pressed it into his palm. Put this in the middle.

Sterling stared at the sea glass, then at the girl who had given it to him. When I grow up, he said, the words tumbling out before he could stop them. I’m going to be rich. Really rich. And I’ll buy you a real ring with a diamond as big as a goose egg. Will wrinkled her nose. That sounds heavy. It’ll be beautiful.

I don’t want a goose egg diamond. She pointed at the sea glass in his palm. I like this one. It’s the color of your eyes. Something shifted in Sterling’s chest. Something warm and terrifying and so fragile. He knew he would spend the rest of his life trying to protect it. I’ll marry you, he said. When I’m rich, I promise.

Willa smiled. A real smile, the kind she never showed anyone else. Okay, she said. I’ll wait. Sterling stared at the security feed. At the woman cleaning his desk, at the ring on her finger. 20 years. She had kept that ring for 20 years. He had become one of the richest men in America, had graced the covers of Forbes and Bloomberg, had built an empire from nothing through sheer force of will.

And in all that time, he had never once tried to find her. Had convinced himself that the boy who made copper rings in junkyards didn’t exist anymore. Had buried that boy under ambition and success and the armor he needed to survive. But she had kept the ring. Does she know? The question hammered at his skull.

Does she know who I am? Is this a coincidence? Is she here for money? For revenge, for something else entirely? He didn’t move, didn’t breathe, just watched as Willa finished cleaning his desk, gathered her supplies, and disappeared from view. His hands were shaking. Sterling Vance had not become a billionaire by acting rashly. He needed more information.

He needed to understand her angle. He decided in that moment not to confront her. Not yet. He would watch. He would test. He would wait for her to reveal herself. The next morning, Sterling left a book on the coffee table. The Velvetine Rabbit. It was old, older than he was, with a worn spine and yellowed pages.

They had read it together at Mercy House, huddled in the corner of the common room, while the other children fought over the television. Willa had cried at the ending. Sterling had pretended not to. He watched through the security cameras as she found it during her morning routine. She stopped. Her hand hovered over the book, trembling slightly.

Then slowly she picked it up and held it against her chest like something precious. She didn’t cry. Her face remained calm, controlled, but Sterling saw her fingers trace the cover, saw her lips move, forming words too quiet for the microphone to catch. And he saw her place the book very carefully, not on the bookshelf where it belonged, but on the pillow of his sofa, the spot where he always rested his head. She knows.

She has to know. But still, she said nothing. Made no move to reveal herself, simply continued to care for him, silently, invisibly, perfectly. The tests continued. Sterling left a Warren photograph tucked into a book. The only picture he had from Mercy House taken at a Christmas party, showing two children grinning at the camera with candy canes in their hands.

One boy with blue eyes, one girl with crooked braids. Willa found it. She studied it for a long time. Then she placed it on his nightstand, angled so he would see it first thing in the morning. He left a radio playing the oldies station they used to listen to through the orphanage’s ancient speakers. She found it and turned up the volume slightly, letting it drift through the house like a memory.

He accidentally knocked over his coffee onto a stack of important documents and watched through the camera as she rushed to save them, blotting the moisture with practice deficiency. When she finished, she placed something small on top of the rescued papers. A peppermint candy, the cheap kind with red and white stripes.

The cafeteria at Mercy House. The candy jar that Sister Mary kept locked in her office. The way they would sneak in during prayer time, hearts pounding to steal two or three mints they would make last for days. If we get caught, Willa had whispered once. I’ll say I did it alone. That’s stupid. Why would you do that? because you’re going to be rich someday.

You can’t have a criminal record. She had believed in him. Had believed in him when no one else did. When he didn’t even believe in himself. And now she was here caring for him. Leaving candy on his paperwork like a message in a bottle. 3 weeks in, Sterling came home to find a bowl of soup on the counter.

Not the fancy kind his previous housekeepers had tried to impress him with. No truffle oil, no Wagyu beef, no micro greens arranged like modern art. This was simple chickenbroth with too much pepper and not enough meat. The kind of soup that the cafeteria at Mercy House used to serve on cold nights, the kind that had tasted like nothing and everything at the same time.

He sat at the counter and ate the entire bowl. Then he sat there for another hour staring at the empty dish, feeling something crack open in his chest that he had spent 20 years keeping sealed. The charity gayla was Margaret Wellington’s idea. Margaret was Sterling’s publicist, a formidable woman who had been nagging him for months to humanize his image after the candle incident went viral.

“You’re trending again,” she told him over the phone. “And not in a good way. Someone found a list of everyone you’ve fired in the last 5 years. The number is not flattering. I don’t care about flattering. You should care about investors. They’re getting nervous about the erratic behavior narrative. So Sterling agreed to host a gala at the Iron Mill.

One night, classical music only, handpicked guest list. What he didn’t anticipate was that Willow would be pressed into service to coordinate the temporary staff. The night of the gala, the iron mill blazed with light. Crystal chandeliers, white roses cascading from every surface. A string quartet playing Vivaldi in the corner. Waiters and black ties circulating with champagne.

Sterling stood at the center of it all, accepting handshakes and small talk with a smile that never reached his eyes. But his attention kept drifting. Through the crowd of senators and CEOs, through the forest of designer gowns and expensive suits, he searched for a glimpse of gray uniform, of dark hair pulled back in a practical ponytail.

He found her near the fireplace, directing a waiter who had nearly dropped a tray of canopes. She moved with the same quiet efficiency she always had, solving problems before anyone else noticed them, disappearing back into the shadows before anyone could thank her. The accident happened just before midnight. Elellanar Whitmore, one of the women who had called Sterling unhinged at her charity lunchon, was holding court near the fireplace.

She was wearing a crimson gown that cost as much as a car and a diamond necklace that cost as much as a house. She was also on her fourth glass of champagne. The glass slipped or she gestured too dramatically or she simply wasn’t paying attention. Whatever the reason, the red wine arxed through the air like blood.

Willa appeared from nowhere. She moved faster than anyone should have been able to move, interposing herself between Elellanor and the falling wine. The liquid splashed across her gray uniform, staining it instantly, permanently. Eleanor’s face went red with embarrassment, which quickly transformed into anger. You clumsy fool.

Her voice cut through the music. Look what you’ve done, Mrs. Whitmore. I apologize. Apologize. You ruined my evening. Elanor’s voice was rising, drawing attention from nearby guests. Do you have any idea how much this moment is worth? More than you’ll earn in your entire pathetic life, I imagine. Willa didn’t flinch.

She stood there absorbing Eleanor’s rage like a stone absorbing rain. And what is that? Eleanor’s eyes had fallen to Willa’s hand to the ring. Is that Is that trash? Are you wearing garbage as jewelry? She grabbed Willa’s wrist, yanking her hand up for inspection. My god, it is trash. Copper wire and a piece of broken glass. I knew servants were desperate, but the ring slipped. It happened in slow motion.

Eleanor’s grip, the twist of Willa’s wrist, the copper ring loose from years of wear sliding free and falling toward the marble floor. Clink. The sound was small, barely audible over the music and the chatter, but Sterling heard it from across the room. It cut through everything.

He was moving before he knew he had made a decision. He crossed the ballroom in a straight line, ignoring the senator who tried to catch his attention, stepping around the waiters who scrambled out of his way. People were staring. Cameras were flashing. Margaret was probably having a heart attack somewhere. He didn’t care. Eleanor was still holding Willa’s wrist, still lecturing her about the behavior of servants, still completely unaware that the most powerful man in the room was bearing down on her.

Sterling dropped to his knees. The marble was cold through his suit pants. He would have bruises tomorrow. He didn’t care. The ring had rolled against the base of a flower arrangement. Sterling picked it up with hands that had signed billiondoll contracts, hands that had shaken with presidents and kings. Those hands were trembling now.

He pulled a silk handkerchief from his pocket, monogrammed, handstitched, and carefully, reverently wiped the dust from the copper wire. The ballroom had gone silent. Even the string quartet had stopped playing. Sterling rose to his feet and turned to face Elanor Whitmore. “Mrs. Whitmore.” His voice was quiet. He never raised his voice. You may purchasethis entire house if you wish.

You may purchase everything in it. You may purchase the ground it stands on. He took Willa’s hand gently, so gently, and slid the ring back onto her finger. But you do not have enough money in all your accounts to purchase the right to touch this ring. He looked directly into Eleanor’s eyes. Its value exceeds the combined assets of every company your husband has ever owned.

Eleanor’s face went from red to white. Mr. Vance, I didn’t. Your car is waiting outside. I suggest you use it. He turned his back on her and faced Willa. She was staring at him with an expression he couldn’t read. Shock, recognition, something deeper that had been waiting 20 years to surface.

Sterling, his name on her lips, spoken aloud for the first time since childhood. Not here, he said. Not now, but soon. He released her hand and walked away. Behind him, the gala erupted into chaos. Willow left before dawn. Sterling found her resignation letter on the kitchen counter in the exact spot where she always placed the cucumber water. Mr.

Vance, I apologize for any disruption I have caused. My presence has become inappropriate given recent events. The ring you recognize belonged to a boy I knew when we were children. He made it for me at Mercy House, and I have worn it everyday since. I did not come here to collect on old promises. I came here because I needed work and I believed I could do the job well. I was wrong.

I wish you every happiness. You deserve more than you know. Willis Sterling read the letter three times. Then he crumpled it into a ball, threw it at the wall, and said several words that would have gotten his mouth washed out with soap at Mercy House. The house was silent around him. Not the peaceful silence of the past weeks, the silence Willa had created. This was the old silence.

The empty silence. The silence of a fortress with no one to protect. He found her address in the employee files. A neighborhood he remembered too well. Row houses with peeling paint. The smell of exhaust and fried food. He parked his old Ford F-150, the first vehicle he’d ever bought, kept in his garage for 20 years, and waited.

She appeared 3 hours later. She was walking home from work, not the shadow service, but somewhere else. a fast food restaurant from the grease stains on her clothes. She carried a plastic bag that probably contained dinner. She stopped when she saw him. For a long moment, they just looked at each other across 20 ft of cracked sidewalk.

“You shouldn’t be here,” she said finally. “The papers will have a field day.” “I don’t care about the papers. Your reputation was built on being cold and ruthless and inhuman.” Sterling pushed off from the truck. I spent 20 years becoming that person because it was safer. Because if everyone thought I was a monster, no one would try to get close.

No one would find out that underneath all the success, I was still just a scared kid from Mercy House who lost the only person who ever mattered. Willa didn’t move. You left,” he continued. “20 years ago, they transferred you to a different home and I woke up one morning and you were gone. No goodbye, no forwarding address, nothing.

They came in the middle of the night. Her voice was barely a whisper. They didn’t tell me either. I know. I found out later, but by then you had disappeared into the system and I was still a kid with nothing. He took a step closer. I told myself I would find you when I made it. When I had the power to search every database in the country and I did, Willa, I found you years ago.

The shock on her face was raw. You knew where I was. I had investigators send me updates, photos. I knew about your mother dying when you were 18, about the night classes you took, about the jobs you worked. I knew everything. Another step. And I did nothing. Why? Because I was a coward.

He stopped close enough to see the tears forming in her eyes. Because I convinced myself the boy you believed in didn’t exist anymore. I’d killed him. Buried him under ambition and success and all the armor I needed to survive. He reached into his pocket. But then you showed up in my house taking care of me the same way you did when we were children.

And I realized that boy isn’t dead. He’s been waiting waiting for you to come back. He pulled out a small velvet box, not black, but worn brown, like something kept for a very long time. Sterling, I’m not giving you a diamond. He opened the box. Inside was a spool of copper wire, bright and new, and beside it, a small pair of wire cutters. You never wanted a diamond.

You wanted this. Will stared at the box. Teach me, Sterling said. Teach me how to make another ring. Let me earn you this time. Let me prove I can be the boy you believed in, not just the man I became. You want to make a ring here on this street. I want to spend the rest of my life making things with you.

rings, a home, whatever you’ll let me be part of.” He took her hand, the one with theold copper ring. I don’t want you to wear my diamonds. I want to wear your copper. I want to belong to you, not the other way around. Willow looked at him for a long moment at the velvet box at their joined hands.

You really planned this? I’ve been planning this since I was 12 years old. I just took a longer route than expected. She laughed. It was a wet sound mixed with tears, but it was the most beautiful thing. Sterling had ever heard. “Okay,” she said. “Give me the wire cutters.” One year later, the iron mill had changed. Plants filled the window sills.

Photographs hung on the walls. Not expensive art, but snapshots from Mercy House. Pictures of two children making copper rings on a Portland sidewalk. A framed copy of the Velvetine Rabbit that had been read so many times its spine was held together with tape. Sterling sat in his study, taking a video call with his board of directors.

His suit was custommade. His watch cost more than a car. On his left hand, slightly crooked and obviously handmade, sat a ring of twisted copper wire with a piece of sea glass at its center. The board members had learned not to ask about it. The door opened behind him and he felt a hand on his shoulder.

Meeting’s running long, Willa said. Give me 5 minutes. Dinner’s ready now. 5 minutes, Sterling. Her voice was patient. The soup is getting cold. He looked at his board members. His board members looked at him. Meeting adjourned, Sterling said, and closed the laptop. Willow laughed and settled into his lap. Their rings clinkedked together. Copper on copper.

When I took that job at the shadow service, she said, I never imagined it would lead to this. When I fired five people over candles, I never imagined it either. That was ridiculous, by the way. I know. He pressed a kiss to her hair. But if I hadn’t been ridiculous, they would have sent someone else.

Willow was quiet for a moment. Do you ever wonder what would have happened if I hadn’t kept the ring? Sterling thought about it. About the cold years, the empty years, the years of building walls, and forgetting how to be human. I think we would have found each other anyway, he said.

Maybe not here, maybe not now, but somehow. That’s very romantic. I’m a very romantic person. You fired people over candles. Romantic people can have standards. She laughed again and Sterling held her closer. Outside the Pacific Ocean stretched toward the horizon. And on the kitchen counter, a bowl of soup was getting cold. The same soup they had eaten at Mercy House with too much pepper and not enough meat.

It tasted like childhood. It tasted like home. And that’s where our story ends. Not with diamonds or mansions, but with two copper rings and a bowl of soup getting cold. Sometimes the richest love stories aren’t about what we gain. They’re about what we never let go. If this story touched your heart, hit that like button and subscribe.

New stories drop every day, each one waiting to remind you that some promises are worth keeping forever. See you in the next one.

News

After receiving the substantial inheritance, I wanted to meet my husband. That night, I told him, “My parents lost their house. They’re moving in with us tomorrow.” He tried to smile, but I could clearly see the distortion in his eyes. The next morning, I walked into the living room and froze. All my suitcases, clothes, and documents were piled up in front of the door. On the table was a divorce paper he had prepared the night before… along with a cold note: “You should leave before they arrive.” I had no idea… the inheritance check was still in my coat pocket.

After receiving the substantial inheritance, I wanted to meet my husband. That night, I told him, “My parents lost their…

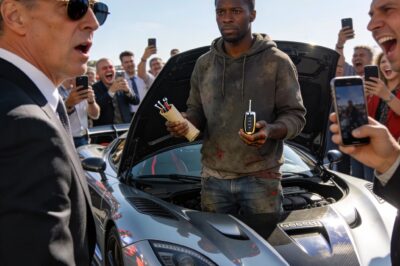

“If you can fix this car, it’s yours,” the billionaire sneered at a homeless Black man who couldn’t take his eyes off his broken supercar — but what happened next left the billionaire completely speechless…

“If you can fix this car, it’s yours,” the billionaire sneered at a homeless Black man who couldn’t take his…

A homeless little girl was reported to the police by a store manager for stealing a box of milk for her two younger siblings, who were crying weakly from hunger — suddenly, a millionaire who witnessed the scene stepped forward..

A homeless little girl was reported to the police by a store manager for stealing a box of milk for…

Two homeless twin boys walked up to a millionaire’s table and said, “Ma’am, could we have some of your leftover food?” The millionaire looked up and was stunned — the boys looked exactly like the two sons she had been searching for ever since they went missing…

Two homeless twin boys walked up to a millionaire’s table and said, “Ma’am, could we have some of your leftover food?” The…

Black maid beaten with a stick and kicked out of billionaire’s house for stealing – But what hidden camera reveals leaves people speechless…

Black maid beaten with a stick and kicked out of billionaire’s house for stealing – But what hidden camera reveals…

While cremating his pregnant wife, the husband opened the coffin to take one last look at her — and saw her belly move. He immediately stopped the process. When the doctors and police arrived, what they discovered left everyone in shock..

While cremating his pregnant wife, the husband opened the coffin to take one last look at her — and saw…

End of content

No more pages to load