An old biker died alone, and that same day his son posted on Facebook: “Finally free of that shame.”

I was the funeral director who handled the arrangements for Juan “The Hammer” Morales , and in forty years of burying people I had never seen such cruelty from a family.

His son, Ricardo Morales , a successful dentist in Guadalajara , came into my office, threw down his credit card and said:

— “The cheapest casket, no wake, just cremate him and that’s it.”

When I suggested that perhaps other family members might want to say goodbye, Ricardo let out a bitter laugh:

— “Nobody wants to remember that that damn drunk ever existed. He preferred his Harley and the bottle to his family. Let him rot alone, just like he lived.”

But the coroner’s report told a different story: Juan had been sober for fifteen years , died of cancer—which he never told anyone—and had only 4,200 pesos in his bank account.

In his wallet there was also a key to a warehouse in Tlaquepaque and a note:

— “When I’m gone – please make sure this gets to the right people.”

What I found in that warehouse made me break all the professional rules.

Because Juan Morales didn’t die forgotten—for fifteen years he had been secretly saving lives , while his own family pretended he didn’t exist.

Inside the storage room were boxes, dozens of them. Each one was marked with a year and filled with letters, photos, and receipts.

The first one, labeled “2008 – Year One Sober ,” contained a leather-bound journal with shaky handwriting:

“Day one without drinking. Ricardo isn’t answering my calls. I haven’t seen my granddaughter Emma in three years. But today I met a guy named Toño at AA. Nineteen years old, desperate for drugs. He reminded me of myself. I gave him my last 400 pesos for food and my phone number. If I can’t save my family, maybe I can save someone else.”

There were photos of Juan with Toño, watching him graduate from the mechanic shop. A wedding invitation where Toño had written:

“I wouldn’t be alive without you, Martillo. Please be my godfather.”

Box after box revealed the truth: Juan had sponsored forty-seven people in recovery . He sold his Harley to pay for a young man’s treatment at a clinic. He lived in a cheap room so he could help others with their rent. The man his son called “drunk” had been sober since the day his granddaughter was born—a granddaughter he was never allowed to meet.

A letter, dated just a month before his death, was from a woman named Sara :

“Martillo, the doctors say your cancer is getting worse, but you still came to my daughter’s graduation. You’ve been more of a father to me than my own. I know you’re hiding your illness because you don’t want to worry us. But we love you. Your AA family, your biker family, we’re all here for you. Let us help you, like you helped us.”

Juan never told them how ill he was. He let himself die in silence in a small room in Tonalá , while his blood relatives lived in mansions ten kilometers away.

His medical records were clear: stage four pancreatic cancer . He refused treatment, not because he wanted to die, but because he didn’t want to spend the money he had saved to help others. His last check, written two days before he died, was for 9,000 pesos so a mother in recovery could buy school supplies for her son.

The last box contained something that broke me inside: hundreds of printed screenshots from Facebook. Every photo Ricardo had posted of Emma , the granddaughter Juan never got to meet. Her first day of school, her dances, her birthdays, her graduations.

Juan had followed her life from afar, saving every single image.

Beneath the photos was a wrapped gift, with a card:

“For Emma’s 18th birthday. I know I won’t be there, but I want her to know that her grandfather loved her, even from afar.”

Inside was the Medal of Valor that had belonged to Juan’s father, a veteran of the Korean War, along with a letter:

“My dear Emma, you don’t know me, but I have loved you every day of your life. I wasn’t a good father to your dad. Alcohol stole years from me that I’ll never get back. But quitting drinking the day you were born was the best thing I ever did, even though I could never be a part of your life. This medal belonged to your great-grandfather. He was a hero. I’m not, but I tried to honor him by helping others. I hope that one day you won’t be ashamed to remember that you had a grandfather who loved you.”

Juan “The Hammer” Morales

The rest was no ordinary funeral:

More than 500 people gathered at the funeral home, including bikers from clubs in Jalisco, godparents and godchildren from Alcoholics Anonymous, teachers, laborers, nurses, lawyers—all rescued by him.

They stood guard of honor and paid for the entire service.

Each person tossed a sobriety coin into his coffin: a final metallic tribute to the man who gave them second chances.

And in the end, Emma , with tears in her eyes, held up the medal:

“My grandfather wasn’t a drunk. He was a warrior of life. And I am proud of him.”

When they lowered the coffin, five hundred motorcycles roared in unison, like a greeting of steel and gasoline that resounded throughout the cemetery.

Juan Morales died alone.

But he was never more alive.

News

“Sir, that boy lives in my house” — What he said next caused the millionaire to break down

Hernán had always been one of those men who seemed invincible. Business magazines called him “the king of investments,” conferences…

A MILLIONAIRE ENTERS A RESTAURANT… AND IS SHOCKED TO SEE HIS PREGNANT EX-WIFE WAITING

The day Isabela signed the divorce papers, she swore that Sebastián would never see her again. “I swear you’ll never…

Emily had been working as a teacher for five years, but she was unfairly dismissed…

Emily had been working as a teacher for five years, but she was unfairly fired. While looking for work, she…

A billionaire lost everything… until his poor daughter, a black maid, did the unthinkable… – bichnhu

A billionaire lost everything, until his poor son, a black maid, did the unthinkable. The computer screen lit up red…

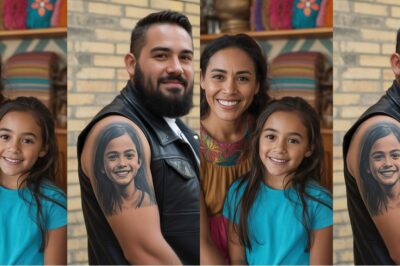

“Eight years after her daughter disappeared, a mother recognizes her face tattooed on a man’s arm. The truth behind the image left her breathless.”

One afternoon in early July, the boardwalk in Puerto Vallarta was packed. Laughter, the shouts of playing children, and the sound of…

As my husband beat me with a golf club, I heard his mistress scream, “Kill him! He’s not your son!” I felt my world crumble… until the door burst open. My father, the ruthless CEO, roared, “Today you’ll pay for what you did.” And in that moment, I knew… the real storm was just beginning.

As my husband, Andrew , beat me with a golf club in the middle of the living room, I could barely protect…

End of content

No more pages to load