In a landmark ruling that will reverberate through American law and politics for generations, the Supreme Court of the United States has finally answered a question left unresolved since the nation’s founding: Can a former president be criminally prosecuted for actions taken while in office?

In a 6–3 decision authored by John Roberts, the Court ruled that a president enjoys absolute immunity for actions taken within the core constitutional powers of the presidency, and presumptive immunity for other official acts. But the decision drew a sharp and consequential line—there is no immunity whatsoever for unofficial or private conduct.

That distinction may now define the future of presidential accountability.

For nearly 250 years, the issue had been largely theoretical. No former president had faced criminal prosecution, and the Court had repeatedly avoided setting a bright-line rule. That era is over. The justices made clear that while the presidency carries immense authority, it does not grant lifelong legal protection once a president leaves office.

The ruling does not place presidents above the law. Instead, it assigns a new and demanding task to lower courts: determining, case by case, whether alleged conduct qualifies as an “official act” or falls into the realm of personal or private behavior. That analysis will now shape every prosecution involving a former commander-in-chief.

For Donald Trump, the decision neither ends nor erases the criminal cases he faces. Instead, it restructures them.

If prosecutors allege actions tied directly to governing—such as exercising constitutional authority over the executive branch—those claims may be shielded by immunity. But if the conduct is linked to personal interests, campaign activity, or behavior outside official presidential duties, immunity likely does not apply at all. In those instances, Trump stands before the courts like any other defendant.

Crucially, the Supreme Court did not decide which of Trump’s alleged actions are immune. That responsibility now falls to trial judges, who must sift through evidence, intent, and context. Prosecutors must still meet their burden of proof. Juries will still determine guilt or innocence. The ruling sets the framework, not the verdict.

Legal scholars note that this is not a victory for unchecked executive power, as critics initially feared. Instead, it is a recalibration. The Court rejected the idea of blanket immunity while acknowledging the need to protect legitimate presidential decision-making from partisan prosecutions. The result is a narrower, more defined doctrine—one that invites scrutiny rather than forbidding it.

The long-term consequences extend far beyond Trump.

Future presidents now govern with the knowledge that leaving office does not automatically insulate them from criminal exposure. Decisions once made under the assumption of political, not legal, consequences may now carry personal risk if they stray beyond official duties. The presidency remains powerful—but not untouchable.

At the same time, the ruling raises practical challenges. Lower courts must now draw distinctions that are often blurry. Where does governance end and politics begin? When does persuasion become pressure? These questions will be litigated intensely, shaping new precedents with every case.

What is certain is that the Supreme Court did not close the door on accountability. It clarified the rules of engagement. The era of theoretical debate is over; the era of courtroom application has begun.

For Trump, the ruling removes one shield while reinforcing others. For the country, it marks a constitutional turning point. Power, the Court made clear, does not come with permanent legal immunity.

And now, the real battles move from constitutional theory into the courtroom—where facts, evidence, and juries will decide what accountability truly means in a post-presidential age.

News

After receiving the substantial inheritance, I wanted to meet my husband. That night, I told him, “My parents lost their house. They’re moving in with us tomorrow.” He tried to smile, but I could clearly see the distortion in his eyes. The next morning, I walked into the living room and froze. All my suitcases, clothes, and documents were piled up in front of the door. On the table was a divorce paper he had prepared the night before… along with a cold note: “You should leave before they arrive.” I had no idea… the inheritance check was still in my coat pocket.

After receiving the substantial inheritance, I wanted to meet my husband. That night, I told him, “My parents lost their…

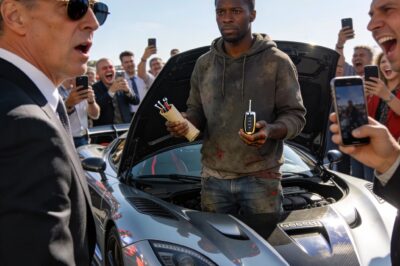

“If you can fix this car, it’s yours,” the billionaire sneered at a homeless Black man who couldn’t take his eyes off his broken supercar — but what happened next left the billionaire completely speechless…

“If you can fix this car, it’s yours,” the billionaire sneered at a homeless Black man who couldn’t take his…

A homeless little girl was reported to the police by a store manager for stealing a box of milk for her two younger siblings, who were crying weakly from hunger — suddenly, a millionaire who witnessed the scene stepped forward..

A homeless little girl was reported to the police by a store manager for stealing a box of milk for…

Two homeless twin boys walked up to a millionaire’s table and said, “Ma’am, could we have some of your leftover food?” The millionaire looked up and was stunned — the boys looked exactly like the two sons she had been searching for ever since they went missing…

Two homeless twin boys walked up to a millionaire’s table and said, “Ma’am, could we have some of your leftover food?” The…

Black maid beaten with a stick and kicked out of billionaire’s house for stealing – But what hidden camera reveals leaves people speechless…

Black maid beaten with a stick and kicked out of billionaire’s house for stealing – But what hidden camera reveals…

While cremating his pregnant wife, the husband opened the coffin to take one last look at her — and saw her belly move. He immediately stopped the process. When the doctors and police arrived, what they discovered left everyone in shock..

While cremating his pregnant wife, the husband opened the coffin to take one last look at her — and saw…

End of content

No more pages to load